How to Solve Absolute Value Equations on the SAT

Table of Contents

On the SAT, you’ll sometimes see questions with absolute value equations. They’re not usually the toughest problems, but they do trip people up if they forget how absolute value works. A sign error or missing a case can cost you an easy point.

Here, we’ll go over the basics of absolute value equations and some straightforward tips for solving them.

Quick Summary

Absolute value represents distance from 0 on the number line. Because distance is never negative, an absolute value is always non-negative.

For example, if a park is the reference point (0), being 5 km west of the park is still a distance of 5 km. We don’t say “-5 km away.” The direction may be negative, but the distance is positive.

This idea is written using vertical bars:

\(|8| = 8\), \(|-8| = 8\)

Both are 8 units away from 0.

Absolute value equations can be grouped into two basic types:

- Simple absolute value

- Absolute value expressions containing variables

Simple Absolute Value

When the absolute value contains only a number, the result is simply the distance from 0. So, the output is always non-negative, regardless of the original sign.

Example: \(|-3| = 3\), \(|12| = 12\)

Here, both \(-3\) and \(12\) are \(3\) and \(12\) units away from 0, respectively. No further solving is needed because no variable is involved.

Absolute Value Expressions Containing Variables

When a variable appears inside absolute value bars, we must consider two possible cases. This is because the absolute value represents distance, which is always positive.

For example, consider the equation:

\(|x – 4| = 8\)

The expression inside the absolute value, \(x – 4\), could be either \(8\) or \(-8\) because both values are 8 units away from 0. To meet this condition, we can set \(x\) as either \(-4\) and \(12\).

- Case 1: \(x = -4\)… \(|-4 – 4| = |-8| = 8\)

- Case 2: \(x = 12\) … \(|12 – 4| = |8| = 8\)

What is an Absolute Value?

The absolute value of a number tells you how far that number is from zero on the number line. It’s written with two vertical bars around the number. For example,

\(|6|=6\)

Since absolute value is about distance, the result is never negative. That’s why, \(|-10| = 10\) just like \(|10|=10\) because both are 10 units away from zero.

Understanding Absolute Value as Distance from 0

Think of absolute value as distance. For example, imagine a central park with two other parks: one 10 km to the west and another 10 km to the east.

You wouldn’t say, “One park is -10 km away and the other is 10 km away.” That sounds awkward, because distance can’t be negative. Instead, you’d say, “Both parks are 10 km away from the central park.”

That shared distance of 10 km is what absolute value represents. Even though the directions are opposite, the distance is the same.

When the Value Inside the Absolute Bars Is Positive

If the number inside the absolute value is already positive, the bars don’t change anything. You can simply drop them.

\(| 10 | = 10\)

When the Value Inside the Absolute Bars Is Negative

If the number inside is negative, the absolute value flips it to positive by multiplying by \(-1\).

\(|-10| = -1(-10) = 10\)

Absolute Value Equations

Absolute value equations are those that contain expressions inside absolute value bars. Solving them means figuring out how to deal with the bars, because absolute value always measures distance from zero and is therefore never negative.

To handle these equations, it’s important to know how to “remove” the bars properly. In general, there are two main patterns you should be familiar with:

How to Remove Absolute Value Bars

Case 1: \(|x| = a\)

By definition, absolute value measures distance from zero, so there are always two possibilities:

- \(x = a\)

- \(x = -a\)

For example, \(|x| = 5\) gives two solutions: \(x = 5\) or \(x = -5\)

Case 2: \(|x – b| = c\)

Here, the expression inside the bars can be either positive or negative. That means we set up two cases:

- \(x – b = c\)

- \(x – b = -c\)

Then solve each equation.

For example, \(|x – 3| = 7\) leads to the following pattern thinking.

- \(x – 3 = 7\) => \(x = 10\)

- \(x – 3 = 7\) => \(x = -4\)

So the solutions are \(x = 10\) and \(x = -4\).

Let’s see how to solve each pattern.

Case 1 : \(|x|= a\)

When an absolute value equation has just a single variable inside the bars, that variable can take on both a positive and a negative value. This is because absolute value measures distance from zero, and both directions give the same result once the bars are removed. For example,

\(|x|= 17\)

In this case, \(x\) can be either -17 or 17, since both numbers are exactly 17 units away from zero.

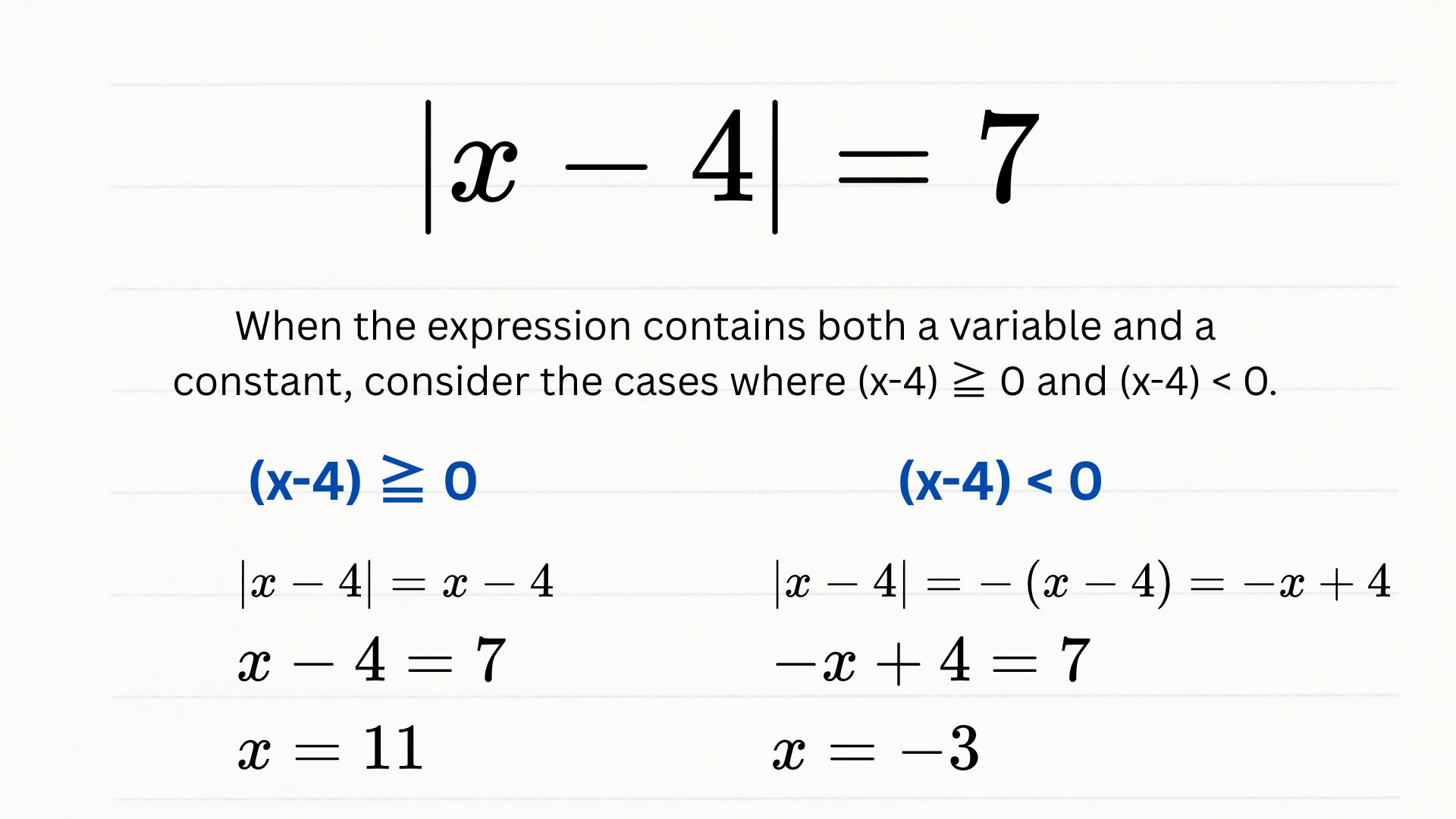

Case 2 :\(|x – b| = c\)

This type of absolute value equation is slightly trickier because the expression inside the bars includes both a variable and a constant. To solve it, you need to consider two cases: one where the inside is non-negative, and one where it is negative.

That’s because if the inside is negative, removing the bars means multiplying by -1.

Let’s check how it works in the following example:

\(|x – 2| = 8\)

Case 1: \(x \geq 2\)

If the inside is positive or zero, so just drop the bars.

\(x – 2 = 8\)

\(x = 10\)

Case 2: \(x < 2\)

If the inside is negative, multiply the whole expression by \(-1\).

\(|x – 2| = 8\)

\(-(x – 2) = 8\)

\(-x + 2 = 8\)

\(x = -6\)

Therefore, the equation \(|x – 2| = 8\) has two solutions: \(x = 10\) and \(x = -6\).

Pattern and Strategy

Case 1 (Simple Calculation)

Explanation

Since the absolute value expression involves a variable, we need to consider two possible cases: \(z < 50\) and \(z > 50\).

If \(z < 50\), the expression inside the bars is positive, so we can remove the bars directly.

\(50 – z = 18\)

\(-z = -32\) => \(z = 32\)

If \(z > 50\), then \((50 – z) < 0\). To handle this, we multiply the inside by \(-1\)

\(|50 – z| = 18\)

\(50 – z\) results in negative value, so multiply the output by \(-1\).

\(-(50 – z) = 18\)

\(-50 + z = 18\)

\(z = 68\)

Therefore, the solutions are \(z = 32\) or \(z = 68\).

Case 2 (Absolute Value and Function)

Explanation

This type of question pattern tests your understanding of both function and absolute value.

Let’s first find the value of \(g(5)\).

\(g(5)=5^{3} -6(5)^{2}+5(5)-20\)

\(= 125 – 150 + 25 -20 = -20\)

Since the result is negative, we need to multiply by -1 when removing the absolute value bars:

\(|-20| = -1(-20) = 20\)

Therefore, the value of \(| g(5) |) is 20.

Case 3 (Number of Solutions)

Explanation

The absolute value of any expression is always greater than or equal to 0.

For the absolute value to equal 0, the expression inside must be 0.

What value of \(x\) makes the expression \(x + 6\) equal 0? Only \(-6\) works!

That means the equation has one solution: \(x = -6\)

Case 4 (Finding Solutions)

Explanation

Remember, when an absolute value expression contains both a variable and a constant and the equation doesn’t equal zero, you need to consider two cases:

one where the inside is positive, and one where it’s negative.

- Case where \(4x+5 \geq 0\)

\(| 4x + 5| = 4x + 5\)

\(4x + 5 = 9\)

\(4x = 4\)

\(x = 1\)

- Case where (4x+5 < 0)

\(|4x + 5| = -(4x + 5) = -4x -5\)

\(-4x – 5 = 9\)

\(-4x = 14\)

\(x = -\frac{14}{4} = -\frac{7}{2}\)

Now we have two solutions: \(p = 1\) and \(q = -\frac{7}{2}\). To find the sum, add them together.

\(1 + (-\frac{7}{2}) = \frac{2}{2} – \frac{7}{2} = -\frac{5}{2}\)

Case 5 (Equations with Multiple Absolute Values)

Explanation

When a problem contains more than one absolute value, the SAT usually makes them identical. This is intentional: if the absolute values were different, the algebra would get too long for a timed test.

A smart way to handle these problems is by substitution. Replace the repeated absolute value with a single variable, say \(a\), and carry out the algebra as if it were a normal equation. Then, in the final step, substitute back the original absolute value and solve for \(x\). This avoids messy mid-calculation steps and keeps your work simple.

We start with \(4|x+3|-|x+3| = 9\).

Let \(a = |x+3|\).

\(4a – a = 9\) => \(3a = 9\) => \(a = 3\)

Now, substitute back \(a = |x+3|\).

\(|x + 3| = 3\)

Since the absolute value contains a variable, we have to consider two cases:

- Case 1:

\(x + 3 = 3\) => \(x = 0\)

- Case 2:

\(x + 3 = -3\) => \(x = -6\)

Therefore, the solutions are \(x = 0\) and \(x = -6\).

Case 6 (Absolute Value Function)

Explanation

We are given the function \(f(x) = |x – 4|\), and we want to find the values of \(a\) that satisfy \(f(6)-f(a) = -2\).

First, compute \(f(6)\).

\(f(6) = |6 – 4| = 2\)

Next, plug \(f(6) = 2\) into the given equation \(f(6) – f(a) = -2\):

\(2 – f(a) = -2\)

Here, we see that \(f(a)\) must equal \(4\) to satisfy the equation. So the next step is to find the values of \(a\) that makes \(f(a) = |a – 4| = 4\).

Since \(|a – 4|\) is an absolute value with an unknown variable involved, we have to consider two cases: when \(a – 4 = 4\) and \(a – 4 = -4\).

If \(a – 4 = 4\):

\(a = 8\)

If \(a – 4 = -4\):

\(a = 0\)

Therefore, the possible values of \(a\) are 0 and 8.